We showed up for her. It’s what family does. My auntie, having had all the responsibility put on her shoulders by her no-good older brothers, was rather alone in it all. Caring for her dying father. I couldn’t imagine how that would feel, needing to be there for someone you love while being forced to be alone on that emotional rollercoaster of loss. And I wish I knew what else I could possibly do for her.

She married into our extended family. On my dad’s side. I knew nothing about her parents, except that they were from Korea. From our shared perspective, my brother and I had no idea why we had to pay our respects and say goodbye to a man we had never met. It was the right thing to do, of course. At least, according to our mother. Though it felt more like a courtesy thing than anything else.

My brother and I didn’t object, but we still questioned the value in “paying respects”, whatever that meant. To be there for our auntie, we understood that and happily obliged, but this… was slightly different. This was a man we did not know. In my mind, I would be confused if people I didn’t know showed up on my deathbed. Simply, I don’t think it’s a gesture I’d appreciate in my current life stage.

Naturally, I had anticipated this to be a rather awkward encounter. Instead, I was surprised by how remarkably touching it was. It was bittersweet in what I would call both a hello and a goodbye. The sun had already fallen when we arrived, and the darkness permeated the surroundings of the hospital. Trees quietly swayed in the distance while the few outdoor lamps lit our way to the entrance.

It was quiet when we got there. But I suppose that’s to be expected at night and in the palliative care ward. Many lights were turned off in various rooms as we proceeded further into the hospital. I felt rather uncomfortable as the silence took over. It was easy enough to have some sort of trepidation and discomfort of other kinds shake you to your core as you visited. After all, there’s just something about being in the hospital, having to walk through those sterile, white hallways.

Well, it wasn’t quite all white. Occasionally, you would pass simple paintings of flowers hung on the walls, providing a comforting pop of colour, but it still felt a little creepy to me. Although we were in palliative care, I’m assuming it wasn’t as off-putting and subdued during the day as it was at night. And once we had reached the nurse’s desk, knowing there was, in fact, civilisation where we were, the nerves quickly faded. My mum had visited before, so we didn’t need to stop at the desk to chat with the nurses.

And just like that, we finally made it to his room. But we stopped in our tracks as we observed that the lights were out through the small window of the door. Our family unit spent a bit of time awkwardly dawdling outside the door, wondering what to do. Eventually, someone emerged from the room. It was a woman I hadn’t met before, and she greeted us at the door, introducing herself as our auntie’s cousin, the niece of the man we were visiting.

She gestured for us to enter the room as we exchanged hellos. We brought mandarins because we knew our auntie liked them, but she was nowhere to be found. And the man we had come to visit was also asleep. It was just bad timing. What were we to do in the meantime? So I did as I always do; as we stood at the door, I looked around the room, observing all the little details I could.

To our right was the man we had come to visit. He was soundly asleep in the bed that perfectly divided the room in half. There wasn’t much happening in terms of decoration, but there was a whiteboard that shared the wall space with the door we had entered. It provided the basic necessities of communication as you would expect in palliative care; the doctor’s name, today’s date, and so forth. To our left was a single sofa, accompanied by the table that usually slides over a patient’s bed. On it was an untouched hospital meal, presumably because the man was asleep and, of course, unable to eat.

As we stood in the darkness of the private room, the bathroom light providing just enough light that we weren’t in complete darkness, someone slowly entered from the hallway. She turned on the side lamp and slowly woke the man up from his slumber. The light was warm and provided much needed colour to the room. The woman was the doctor who had come to inform him of the small checks they would make later that evening. And his niece translated everything so he could understand.

After we watched that small interaction unfold, my brother and I brought ourselves to his bedside and greeted him awkwardly. He smiled and spoke to us in English, “long time no see”. He was cheerful in his response, but it took no time for his smile to falter, as if a sudden wave of emotion had overcome him. Tears welled up in his eyes and streamed down his face as he continued trying to get words out. On the surface, he looked healthy—like a regular man who had lived a long and fulfilling life.

I have no memory of meeting this man, but I could only wonder what he was thinking when he saw us. It’s a reasonable assumption that he had probably met us when we were far younger. Did his life flash before his eyes as he remembered us as children all those years ago? So much time has gone by and now he’s in an unfamiliar place. Undoubtedly unsettling and uncomfortable.

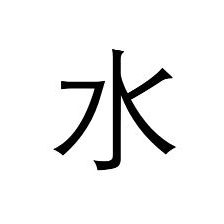

Everything else he said to us after his greetings was spoken in Korean. We are far from fluent—and I can’t speak for my brother’s proficiency or experience on this matter—but I was surprised by how much I understood. And it was so meaningful. The feelings of discomfort in unfamiliarity and not knowing what to do or say was slowly extinguished with a strange air. It felt heavy in my throat and lungs as I held back tears listening to this man.

Among the sorry’s and thank you’s that he whispered to us, I held onto his words through his niece’s translations with a sad smile. He shared a story with us about a life lived with regrets. Instead of working so hard, he wished he had taken better care of his health before it was too late. It felt a little ironic. I, who had struggled with the thought of work, wealth, and worth, possess what this man did not. Health. And it flipped some of the thoughts I had on its head. A sense of relief came over me, but it was accompanied by some sadness and guilt.

By no means did this man really know me. Past the assumed meeting sometime in my childhood, we weren’t acquainted any more than that. Yet, the impact of his words was significant. Internal struggles I had not shared with anyone seemingly dissipated from my shoulders. The intangible pressure simply became lighter in the face of… well, death. And it was in this dimly lit hospital room on a random night that led me to re-evaluate everything with which I had been at odds.

I had been taking my recent good health and other freedoms for granted. This obligatory visit has left an irreversible mark on me. His words held a weight that could only be explained by the richness of his lived experiences. They were poignant and those short minutes with this man were incredibly moving. I’m grateful for the opportunity to have met him, even in his last days. Should I see him again in heaven, I would like to have a long conversation and learn all about his life on earth.

Rest in peace.